Neutrinos¶

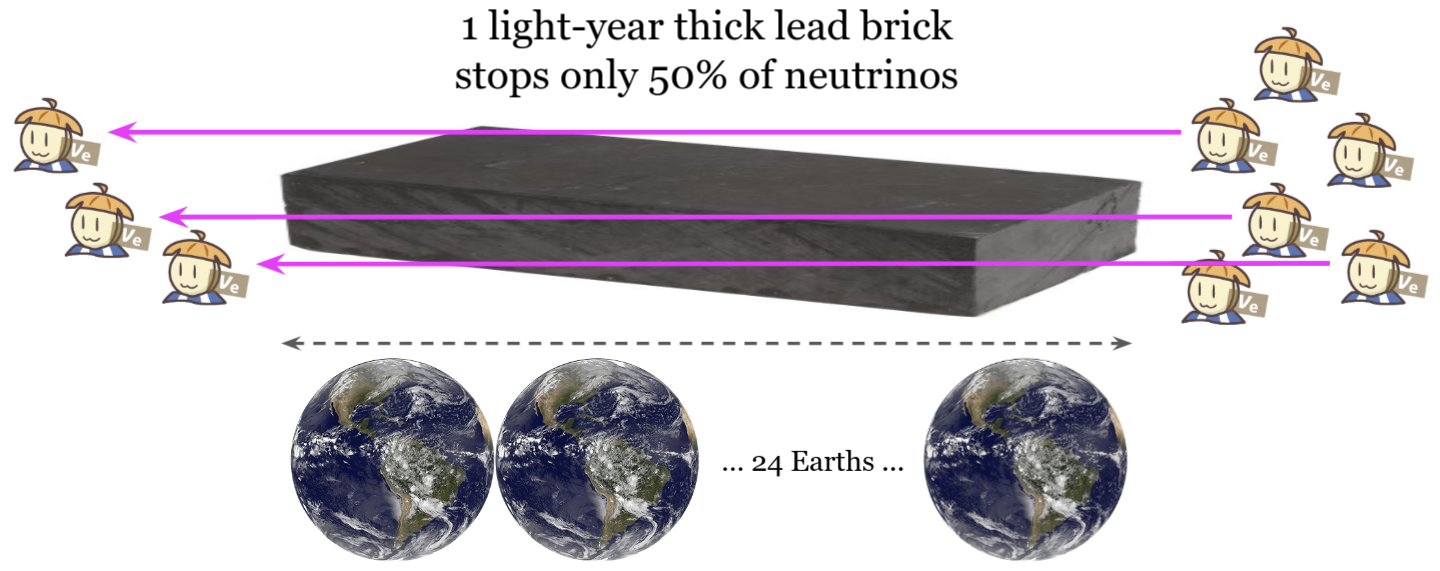

Neutrinos are only weakly interacting, and it is hard to detect. How ard to detect? To put into a perspective, a light-year thick lead has 50% chance of stopping (or “catching”) neutrinos. This is one reason why neutrinos are one of the least understood particles and lots of mysteries!

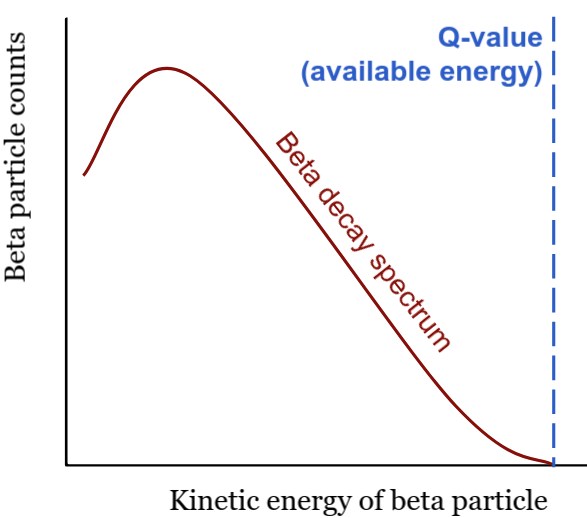

Neutrinos were first postulated by Wolfgang Pauli in order to explain a nuclear beta decay in 1930 (original letter + translation here ). Three major nuclear decay modes include an alpha, beta, and gamma decays, emitting an alpha particle (Helium nucleus), an electron, and a gamma ray (photon) respectively as a decay product. Detecting the kinetic energy of an alpha particle or an electron is relatively straightforward using an experimental apparatus because they are electrically charged. An alpha decay is a two-body decay. The conservation of energy and momentum results in a mono-energetic peak of an outcoming alpha particle, unique to a parent isotope (this fact is used to identify radioactive elements in the alpha-particle spectroscopy). A beta decay spectrum, on the other hand, is wide and spread, nothing like a mono-energetic peak observed for alpha particles. Back in 1930, however, physicists observed only an electron and resulting nucleus as decay products. A famous physicist Niels Bohr even suggested that, perhaps, energy is not conserved in an individual beta decay process. Pauli’s attempt was to introduce a neutral, rarely interacting ghost particle (practically undetectable at that time) in a beta decay. With this particle, known as a neutrino today, a beta decay is a three-body process and could explain a wide energy spectrum of a decay electron. Furthermore, this particle considered to have zero or undetectablly light mass. For a neutrino to be emitted, at least the energy worth its mass needs to be taken away from the process. Yet, the observed beta decay spectra suggest that an electron may take away all of the available energy (within the experimental resolution). This implied that the mass of a ghost neutrino must be zero or less than the resolution limited by the experimental aparatus.

Fast forward many decades, we know a lot more about neutrinos today. There are three types of neutrinos (electron, muon, and tau flavor of neutrinos). A muon-neutrino with energy more than the muon mass can interact with a neutron to produce a muon and proton (but it cannot produce an electron). Similarly, an electron-neutrino can produce an electron through the same process and would not produce a muon. This is called a lepton flavor conservation in an weak interaction. Furthermore, neutrinos turned out to be massive particles (i.e. they have non-zero mass) and exhibit an intriguing phenomenon, called neutrino oscillation, through which a neutrino can change its flavor (i.e. an electron neutrino could become a muon neutrino). Multiple Nobel prizes have been awarded to neutrino physics experiments including the first detection of neutrinos by Reins and Cowan to the most recent, discovery of neutrino oscillation and massive neutrinos by Super-Kamiokande ans SNO experiments.

Why studying neutrinos?¶

Despite the progress made in the recent years, many questions about neutrinos remain unanswered. We know neutrinos have mass and the relative mass difference among three neutrinos. But what is their absolute mass scale? Do neutrinos and anti-neutrinos behave same in neutrino oscillation? Is a neutrino its own anti-particle? A possible consequence of answers to these questions is an explanation for why our present universe is dominated by matter particles and filled with little anti-matters. Where did anti-matters disappear after the Big Bang, at which there should have been 50-50 fraction of matter and anti-matters? Neutrinos might be a key to explain why we exist today.

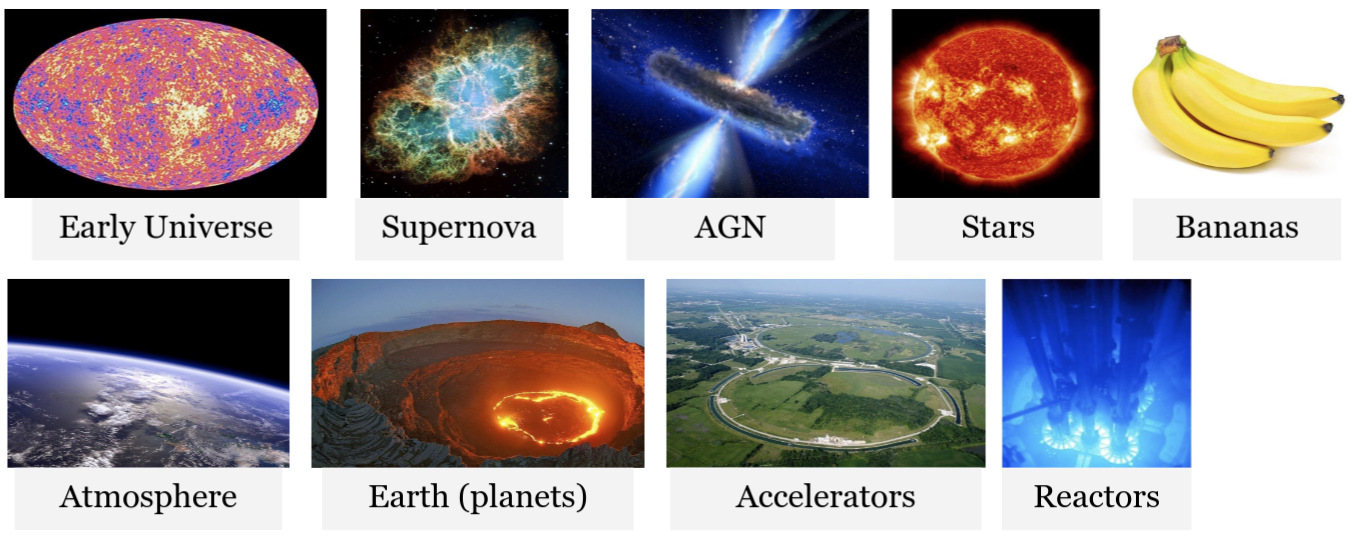

Furthermore, understanding how neutrinos are produced and travel through the space-time (during which they participate in the oscillation) helps us understand many physics phenomena in our universe. While it is difficult to detect, neutrinos are the second most abundant particles in the universe known to date (the most abundant are photons) and they are produced in everywhere: the beginning of the universe, supernova, stars including the Sun, cosmic rays, nuclear decays inside the Earth, nuclear reactors and particle accelerators, and even from bananas. To put into a perspective, there are about 65 billion neutrinos from the Sun passing through your thumb nail every second. That’s just the Sun!

There are so many of them, and they carry information about the physics behind their source. If we understand how they are produced + how they propagate to our lab, and if we could efficiently detect them, we can study the physics of their source. It is just like how you observe light (photons) and study about stars in the nightsky. Unlike photons, that can be easily blocked by an obstacle between the source and an observer (us), most of neutrinos carry “raw” information without any interruption thanks to its ghostly nature (i.e. participate only in the weak interactions). A great example is the Solar Model, our understanding of how the Sun burns today, which was confirmed by observing neutrino flux from the Sun. Through this process, the neutrino oscillation physics was also studied in details and a great progress was made (a half of a Nobel prize awarded to the SNO experiment).