Detecting neutrinos¶

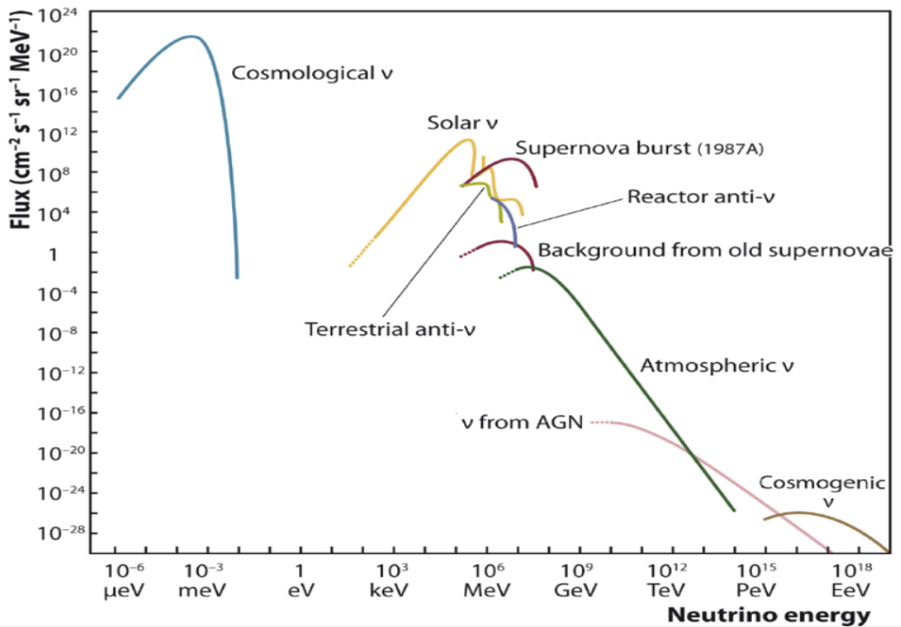

Despite all the excitement about neutrinos, we cannot learn anything without being able to detect them, which is a challenging task because they interact so rarely (recall a one-light-year thick lead brick)! It is unlikely to have a single ultimate detector design for all types of neutrinos in the nature we wish to study. The plot below shows the flux (i.e. the intensity) and the energy of neutrinos coming from various sources. Both axes spans a large region in the logarithmic scale. Detecting them all efficiently is extremely challenging and would certainly require multiple detector technologies. Here, we will briefly discuss basic design principles for neutrino detectors used for studying neutrino oscillation physics and go over a few example detectors.

First neutrino detection¶

Although neutrinos rarely interact, we can take an advantage of the fact that they often come in a large number (i.e. billions from the Sun through your thumbnail). Even if only one in a million neutrinos interact, if we place our detector under a flux of billion neutrinos passing through, we expect about 1,000 neutrino events!

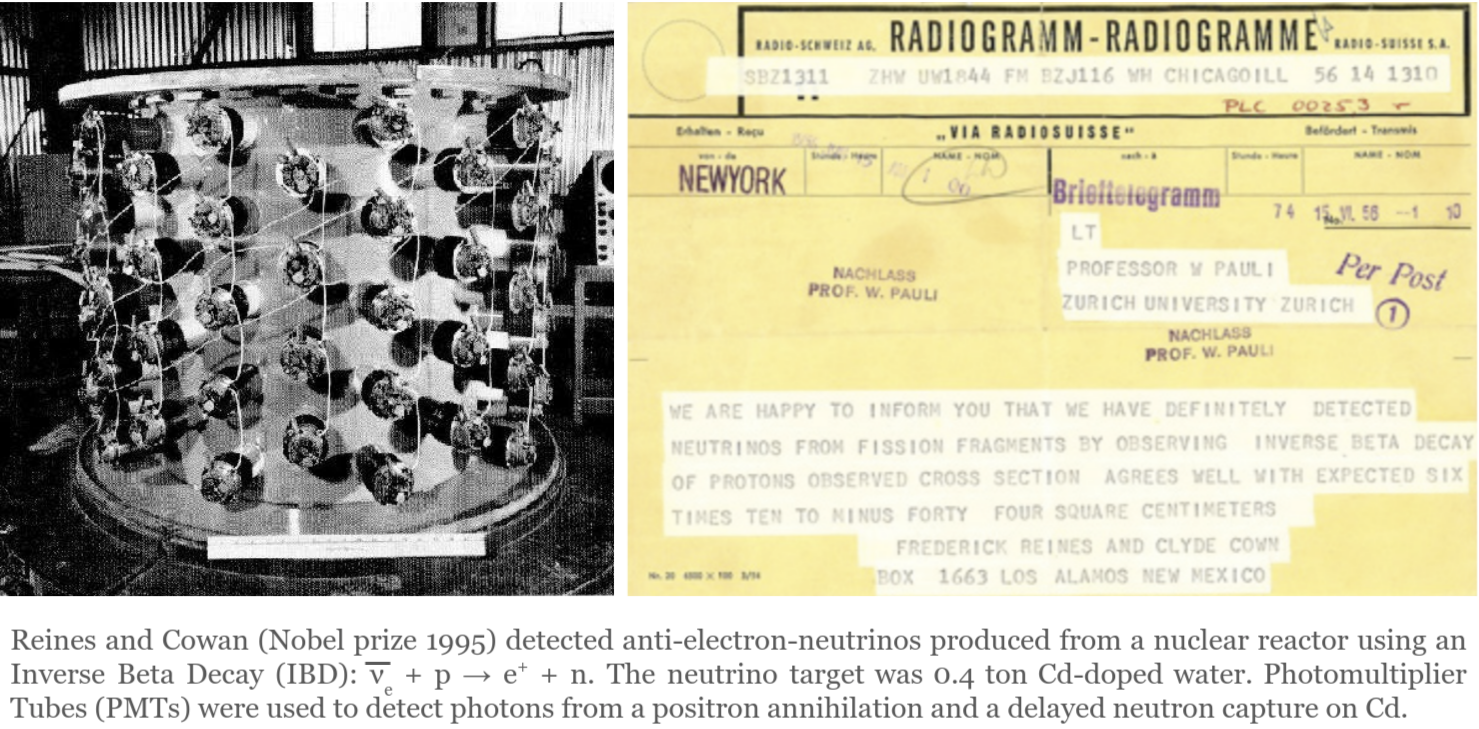

The very first detection of neutrinos by Reins and Cowan, reported in 1956, followed the same principle. In their experiment, they looked for electron anti-neutrinos produced by a nuclear reactor core. The detector was placed in the underground, close to a nuclear reactor core, with enough concrete shielding to avoid other radiations such as neutrons and gamma rays. They used Cadomonium-doped water as a target in their detector. Electron anti-neutrinos interact with a proton in the water and produce a positron and a neutron, a reaction called Inverse Beta Decay (IBD). The positron annihilates with an electron immediately, emitting two gamma rays. Cadominium in the water captures a neutron micro-seconds later to emit high energy gamma rays. These gamma rays were then detected by Photomultiplier Tubes (PMTs) and liquid scintillator tanks sandwhicing the target water tank. By looking for two signals (i.e. a positron annihilation and a delayed neutron capture) in time coincidence (micro-seconds apart), they could reject much of the background signals. This method (IBD in a liquid scintillator) invented by Reins and Cowan is used by present neutrino experiments. You can read more interesting details about Reins-Cowan experiment here.

Detector design principles¶

Much progress has been made in the R&D of neutrino detectors alongside the advancement in our understanding about neutrinos, including the discovery of neutrino oscillation. An important key scalability: we want a detector technology that can be scaled to a large volume, hence increasing a chance of detection. For studying neutrino oscillation, there are additional factors. Neutrino oscillation is characterized by the energy of neutrino and the distance of travel. So, the detector needs a good energy resolution to be able to infer the neutrino energy with high precision, and the location needs to be measured accurately. Furthermore, in order to identify that a neutrino flavor has oscillated (or not), we need a detector with a capability of particle type identification so that we can distinguish electron and muon neutrinos. So three important factors:

A scalable (in volume) detector technology

Good energy resolution

Capability to identify particle types

Two-detector design¶

There is another important design pattern that is applicable for oscillation experiments with an accessible neutrino source (e.g. a nuclear reactor core or a particle accelerator). To quantify a neutrino oscillation, we need to quantify how many neutrinos changed the flavor after the oscillation took place. This can be done precisely if we place one detector next to a neutrino source (near detector), and another detector separated by some distance (far detector) for oscillation to happen. The detector mesures the neutrino flux per flavor before the oscillation, and the far detector measures after. Then the oscillation can be quantified by taking a difference. Experiments our group participate also follow this two-detector design including the Short Baseline Neutrino (SBN) program, Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), and T2K.

Example: Super-Kamiokande¶

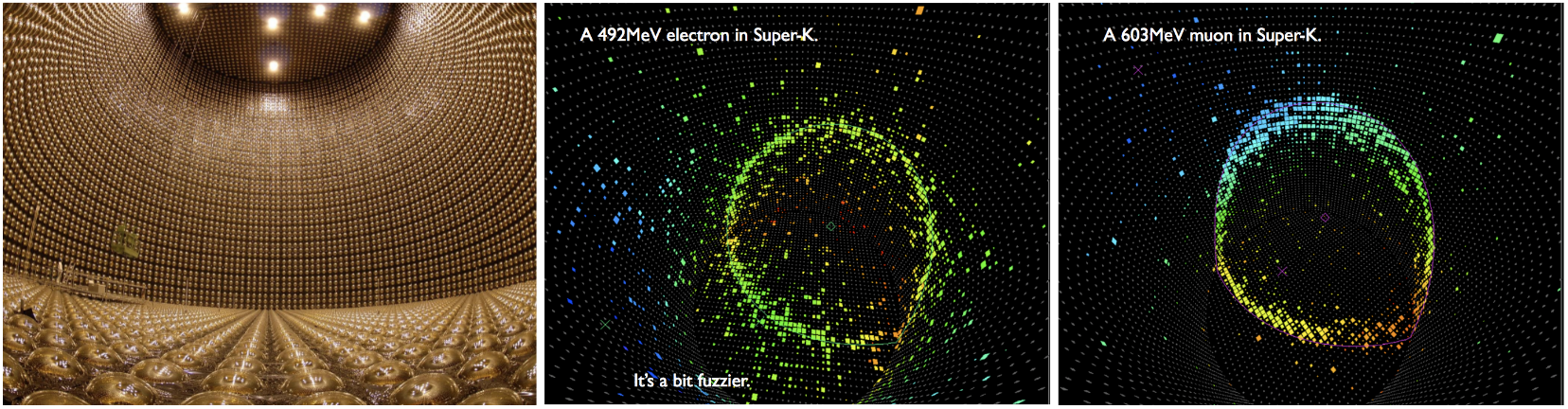

The Super-Kamiokande (left in the image below) is a modern Water-Cherenkov detector (i.e. detects Cherenkov light produced by charged particles traversing in a medium). The detector consists of the target, 50 kiloton of purified water, and 11,000 large PMTs surrounding the target. This is a huge leap from the detectors employed by Reins and Cowan! PMTs are sensitive to photons with a certain band of wavelength (typically overlapping with the visible wavelgnths to human eyes). The photons emitted by Cherenkov radiation has a wavelength determined by an opening angle between its direction and the motion of the emitting particle. As a result, only PMTs that are within the certain angular range will detect photons within their sensitive wavelength, and this can be seen as a Cherenkov ring in the image below. An electron is 200 times lighter than a muon, and its direction is more affected by scattering process. This results in a fuzzier ring for electrons (below middle) compared to muons (below right), and this allows the Super-Kamiokande detector to distinguish those two particle types. Super-Kamiokande serves as a far detector for the T2K neutrino oscillation experiment in Japan.

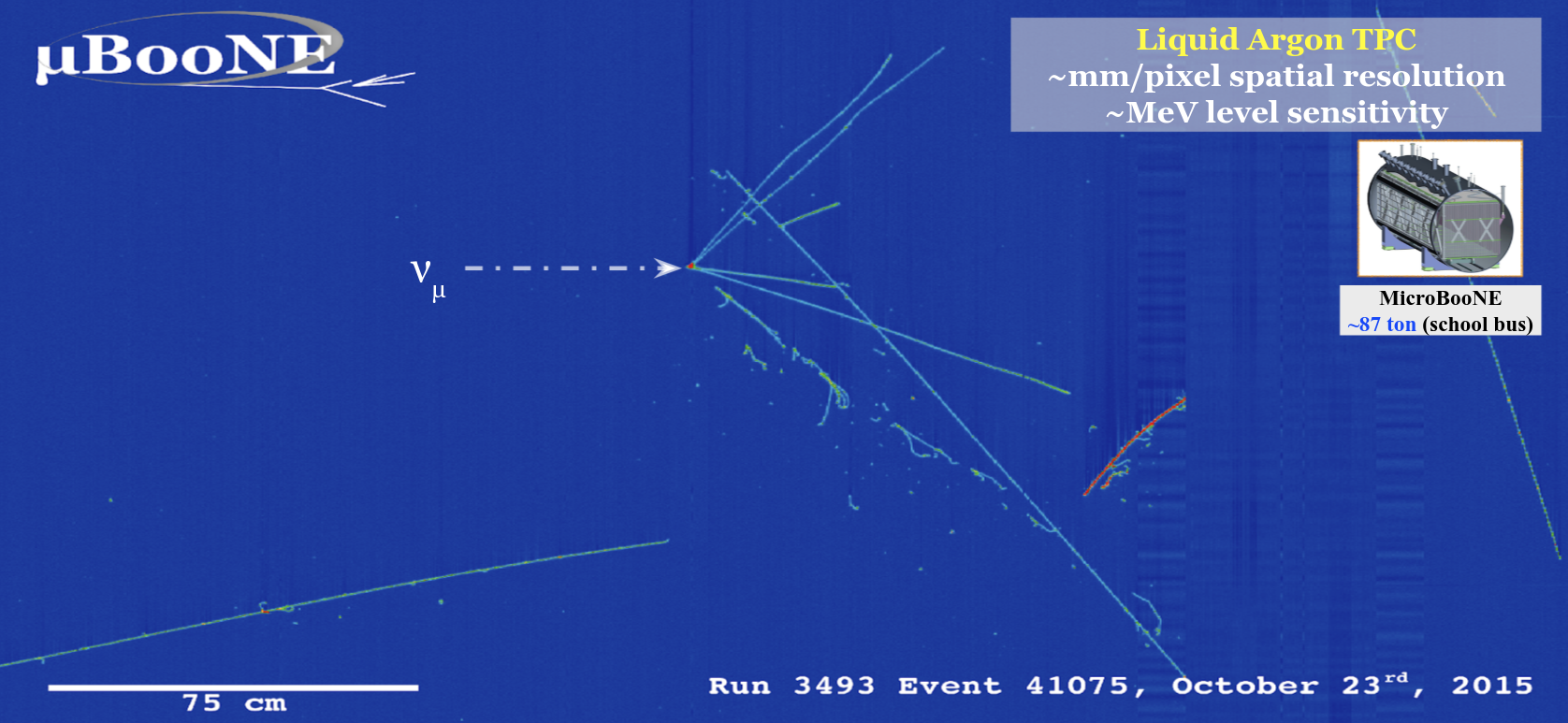

Example: MicroBooNE¶

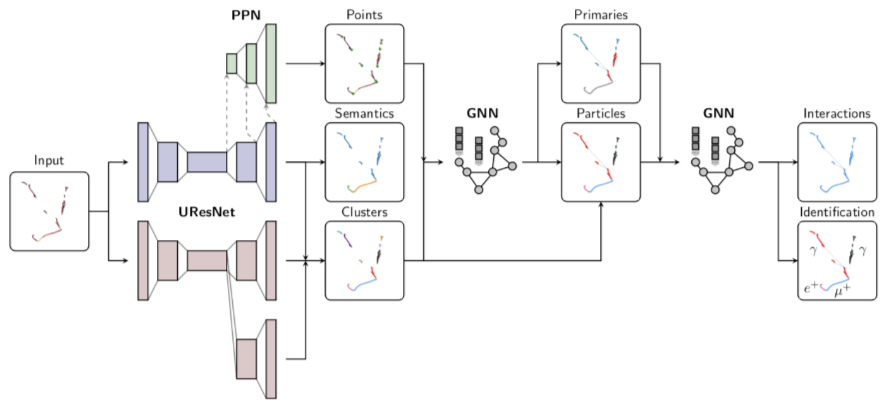

Liquid Argon Time Projection Chamber (LArTPC) is another detector technology that is actively pursued for neutrino experiments today. Like the Water Cherenkov detectors, LArTPCs are scalable in volume (Ar is cheap!), and have a good capability in reconstructing the energy and type of detected particles. As you can see in an example data taken by MicroBooNE LArTPC experiment below, we can observe the details of a particle trajectory including small branches of atomic electrons knocked out along a long trajectory (likely a muon or pion). The color scale of an image reflects the amount of energy deposited per pixel, and is used to infer the energy loss per unit length, or dE/dX, which is a function of particle mass (hence type) and momentum. LArTPCs can record a lot more physics features than the Water Cherenkov detectors. While it is truly beautiful, a big image data with every detail of complex particle trajectories also presents challenges in efficiently identifying neutrino interactions. To put into a perspective, The MicroBooNE detector records 87-tonne volume in an image of 80 mega-pixels. The Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE) will be recording 40 kilo-ton of LAr volume. Our group leads the development of a high quality and efficiency data analysis techniques for LArTPC detectors using Computer Vision and Machine Learning.